- Home

- Yasmine El Rashidi

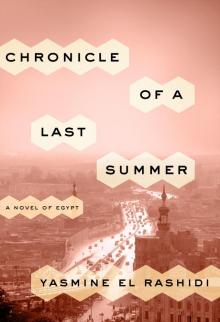

Chronicle of a Last Summer

Chronicle of a Last Summer Read online

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2016 by Yasmine El Rashidi

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Tim Duggan Books, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

crownpublishing.com

TIM DUGGAN BOOKS and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: El Rashidi, Yasmine, 1977–author.

Title: Chronicle of a last summer : a novel of Egypt / Yasmine El Rashidi.

Description: First edition. | New York : Tim Duggan Books, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2015050541 (print) | LCCN 2016015049 (ebook) | ISBN 9780770437299 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780770437312 (softcover) | ISBN 9780770437305 (ebook) | ISBN 9780770437305 (ebook/epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Young women—Egypt—Fiction. | Families—Egypt—Fiction. | Egypt—Politics and government—1981—Fiction. | Mubārak, Muhammad Husnī, 1928—Fiction. | Egypt—History—Protests, 2011—Fiction. | Political fiction. | Domestic fiction. | BISAC: FICTION / Literary. | FICTION / Historical. | GSAFD: Bildungsromans. | Historical fiction.

Classification: LCC PS3605.L147 C48 2016 (print) | LCC PS3605.L147 (ebook) |

DDC 813/.6—dc23

ISBN 9780770437299

ebook ISBN 9780770437305

Cover design by Tal Goretsky

Cover photograph by A. Abbas/Magnum Photos

v4.1

ep

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Part One: Summer 1984, Cairo

Part Two: Summer 1998, Cairo

Part Three: Summer 2014, Cairo

Acknowledgments

About the Author

for Seif, and for Julie

The house was blistering. Mama had drawn in and closed the wooden shutters hours earlier. Damp towels lay rolled on windowsills. The heat still seeped in. She now sat at one corner of the sofa, gray phone receiver in one hand pressed to her ear, plant mister in the other. She sprayed her face at intervals. Mama had always said the heat never bothered her. It was how she was made. That summer had been different. I sat at her feet staring at the muted TV screen, getting up and flipping between channels. Channel One. Channel Two. The third channel stopped its broadcast at one p.m. There were only two programs for children. I flipped hoping I might find something. In the corner of the room was Granny’s old metal fan. It clicked and whirred, drowning out Mama’s English-laced Arabic. I could make out none of the conversation, except to take note when she switched to French. It was the single language she spoke that I still didn’t know. She seemed to use it more often that summer.

I had no way of measuring time, but we sat like that for hours. Ossi appeared now and then at the doorway and meowed. Mama ignored him. He was gray with long hair. Mama had said it was a bad idea to have a Persian. If one were to have a cat, it ought to be a local, a baladi. Baba said let the girl have what she wants. He brought him home in the palm of his hand one day. The day I turned five. I wanted to call him Fluffy. Mama said Fluffy was not a proper name. She called him Osama. Baba never touched him again. He was allergic, even though his hands were huge. He would put me onto his palm and lift me into the air. I would sit perched like that as he watched TV. I missed Baba’s hands, especially his giant fingers. He would make a hook out of them and pretend he was hooking my neck like a fish, pulling me close to kiss him. I loved the way Baba smelled. You could smell him everywhere in the house, especially on the sofa. Even when he went on trips his smell would still be there. It had gone away this time. I was waiting for him to come back. Every day after school I would get out my class notebook and turn back the pages to the one with the green star in the corner for the day he left. I would flip to the next page. Then the next page. I counted until I reached fourteen. I kept counting until the page we used in school that day. Fifty-seven. I couldn’t tell how many extra days it had been.

It was July but I was still in school. My cousins had four months of summer holiday. Sometimes five. We only had one. It was the English school. In Arabic school there was no homework. The teachers didn’t make enough money to correct it. I wanted to be in Arabic school like my cousins. It wasn’t fair. Mama shook her head. Four months of summer would make of me a listless child. Too much holiday was bad for character, Mama said. Poor posture was also a sign of it. That summer it had become a concern. Mama finished her phone call and told me to walk across the room with a book on my head. She made me do this each afternoon. I made it like a game. I especially liked when the book began to slip. It tilted to the right and I felt it. I bent my knees. It was as if I were going to jump, take off, but I slid back up, pushing my right shoulder. It slipped back into place. It only ever slid to the right. The next time it fell. It was an old book with a thick blue cover. It said SUEZ. It hit the parquet floor with a thud. I glanced back at Mama nervously. I saw she wasn’t watching.

It was a school night but Mama had stopped paying attention to time. I stayed up late with her. I took out my sketchbook. I drew. Fish. The bottom of the sea. Myself swimming with them too. The teacher shook her head. She told me I had to watch myself, I was a dreamer. I turned to the TV. They were replaying pictures of starving children in Ethiopia. Every day we watched them. Mama had a friend from Ethiopia. She taught me how to count to ten in their language. Whenever she came for lunch she said a prayer before she ate. She said it was for the famine. She told me to look at the food on my plate and remember how lucky I was. With each bite I should remember Ethiopia. Maybe I should send my lunch to Ethiopia? Every time I see the starving children on TV, I say a prayer. I don’t know what to say but I put my head down like Kebbe and move my lips. I then say Allahu Akbar, like Grandmama does. I whisper so that Mama can’t hear. There are also starving children in Cairo, but they never show them on TV. I see them in the streets on the way to school. They sell lemons at the traffic light. Three of them sleep in a cardboard box under the bridge next to our house. One of them has hair like mine. I know if I stand next to her the tops of our heads will meet. I want to talk to her but when I smile and start to roll down the window one day, Mama tells me to look away. I’m not to encourage such behavior. I turn my head down. I look at her from the corner of one eye.

After the famine they replay the documentary about Sadat. They show him with his wife and children. They show him meeting important people. They show him at the parade where he was killed. I was three and three-quarters when they killed him. It was the day of Mama’s birthday. We were watching TV. Mama put her hands to her mouth. Baba stood up. They gasped, then were silent, then Mama started saying Quran. I was too young to remember. Baba told me everything about Sadat. He did very good things and very bad things. Making peace with Israel was very bad, Baba said. He didn’t like the Israelis. They were buggers. Mama grumbled that he shouldn’t use that word again. They wouldn’t tell me what buggers were but I knew they were bad. Everyone we knew hated the Israelis, except for one of Baba’s cousins. Baba raised his eyebrows at him and shook his head. He turned and looked into my eyes. He had signed his name to fight in the war. It was important to be loyal to my country.

Next they play the video of the new president, Mubarak. He was sitting next to Sadat when he was killed. They said it was a miracle he wasn’t killed too. It was something from God so they made him president the next week. Now

he was always opening a new factory. They show him cutting the ribbon and shaking people’s hands. Baba said it was the making of a pharaoh. I got up and changed channels. Channel Two. The black-and-white film with Ismail Yaseen. It screened on Thursdays after school. They would play things in order and many times over. The TV was mostly boring but Mama only let me watch videotapes on weekends. She said only boring people got bored. I felt bored every day after school. I got up and put the last tape into the VCR. I hit rewind. It made a sound like an airplane passing. Mama tutted. When it finished rewinding it clicked three times. I pressed eject. It made a rumbling noise then squeaked as it came out. I put it back in its case and onto the shelf next to the five VHS tapes Baba said were for me. There were other tapes on the higher shelf. They were adult. I went back to Mama’s feet. She was on the phone changing languages between English and Arabic and French. I heard her say it was the only thing she had. I knew she was talking about the house. They can forget it. She switched to French and I heard her say Baba’s name.

I bring out my writing notebook from school. We have to write a story from our day. I draw a blue frame around the page. In one corner I put the date. I count down four lines and write: I am sitting with Mama waiting for the power to cut. At the bottom I draw a picture of Mama on the sofa. I draw a vase with sunflowers like in the films. I watch the flickering TV screen until the power cuts. We don’t say anything when it happens. It cuts every evening then there is silence. Even from the street all sound stops. We stay in the living room, not moving, until it comes on again. Some days Mama gets up and moves to the balcony. She takes the phone. The cord is so long it also reaches the bathroom. Usually she just stays on the sofa misting herself. The cuts last one hour. Sometimes two. Some days, in the winter, they skip a day. We all have power cuts. Only three of my friends at school don’t have power cuts. Their fathers are important. One of my best friends has a grandfather who is important. He is dead now, but they are still important. They never have power cuts. Mama also says the Sadats never have them. They are related to us, but not close enough for our power cuts to stop too.

The lights come on again. The TV flickers then screams with sound. Mama sighs and shakes her head. I press mute. She gets up and comes back with a tray. I have the same dinner every night. Every night Mama tells me to chew slowly. I count. Twenty, twenty-one, twenty-two. Sometimes I reach thirty. Baba didn’t mind how I ate. He liked food more than Mama. Once, after Baba left, Aunty came to the house and told Mama she had to make an effort with her food. That day Mama was crying. I gave her a tissue and stood next to her. She patted my head. She didn’t seem to make an effort after that. Mama was thin. Nobody else we knew was thin like Mama. Except on TV, but only in American films. I take a bite of my grilled cheese sandwich.

After a while Dallas comes on Channel Two. It runs six nights a week and everyone watches. I go to the kitchen balcony and watch people watching in the building next door. Everything is dark except the screens. I imagine myself in the flat with the three sisters. I wish I had sisters. I go inside. Mama asks me to turn up the volume. Her dinner tray is on her lap. I watch Mama chew. She chews slowly, like Nesma did. Mama said that Nesma dying was like losing a child. She was my aunt, but they said she was like my sister. She had Down syndrome. It was also about hormones, but not Baba’s kind. That kind was only for men, to make them big. People told Mama they admired her. One lady said that anyone else would have hidden Nesma away. I imagined her in a cupboard. How would she eat? Some days after school I would sit in my cupboard imagining I was hidden away. I waited for them to find me. Baba did, but after he left nobody took notice. Mama did everything for Nesma. I heard her crying on the phone once because someone had made fun of Nesma at a restaurant. She said people think Nesma doesn’t understand. I knew she understood. I wished I had known last summer would be our last holiday together. I came home from school one day and at the gate I heard my name. I looked up. It was Nana, Mama’s friend, in the building across the street. She was on her balcony, waving. Come. Her building had an old glass elevator that rattled as it went up. You could see all the wires. They were black and greasy. I took the steps. I never remembered what floor they were on, but Abu Ali their neighbor had Quran written on his door. Mama and Nana said this was terrible. Sometimes when I saw Abu Ali he would tell me Al Salam Alaykum. Mama told me I should never respond. Only nod your head. Since when do we say Al Salam Alaykum. If you answer, say Sabah El Kheir. Grandmama was always reading Quran and saying Al Salam Alaykum. I told Mama. She said I was too young to understand. I reached Nana’s floor. The door was open. She told me to come inside, then hugged me. Nana never hugged. Bad news. Nesma had died and I would be staying the night. I screamed. I screamed so hard my voice stopped, like in the dream. I wanted to go home. She made me sit at the dining table and put a plate with rice and okra and escalope panée in front of me. She told me I had cried enough. Mama didn’t let me eat escalope panée. I ate it quickly. I fell asleep that afternoon and woke up again after eighteen hours. Nana said she had never seen anyone sleep so long.

When Nana let me go home, there were many people in the house dressed in black. Mama had on a white scarf. A man was sitting cross-legged on Granny’s armchair reading Quran. Mama never let anyone put feet on the furniture. Our house was Granny’s house. Mama was born in it. It was two floors and like a castle. The garden was filled with trees. We had mangoes, figs, tangerines, sweet lemons. There was also a tree that grew from the seeds Mama threw out of the window when she was a little girl. Custard apple. We even had a coffee tree that Mama’s friend brought us from Ethiopia. Under it was a wishing spot. Any wish you made would come true. Baba had built me a playhouse in the corner. It was wooden and painted red. The Nile was across the street. We could see it from the upstairs balcony. Mama said our house was plain but unique. Baba called it modern. People would take pictures. There were little windows at the top, near the roof, tiny, in threes, like secret rooms. There was a round window on one side, and a triangular window on the other. There was a secret box of treasures that Granny hid in the staircase when the house was being built. Granny lived downstairs with Nesma and I would come home from school and find their floor full. People I knew. People I didn’t know. We would have lunch in Granny’s dining room and Mama and Baba would come down too. Granny would sit at the end of the long table. She would ring her silver bell and Abdou would come in from the kitchen. Abdou was dark and from Sudan. He would go on holiday every summer and bring us back peanuts. Sometimes I would sit in the kitchen as he cooked. Abdou was always making maashi. He lined green peppers and zucchini on the counter and went through them, one by one. He held each vegetable like a tennis ball and with a knife made a circle on the top. With his special sharp-edged spoon he would scoop, bringing out the insides. He taught me. It’s all in the wrist. Making dessert was the best. We picked mangoes from the garden that Abdou cut into pieces and put in the freezer. I licked the skins that were left. Abdou would tell me stories about Sudan. Once, Egypt and Sudan were like one country. It was because of the English. They made some countries theirs. They divided other countries. Abdou didn’t like the English or the Americans. He told me they were trouble. If there weren’t any English or Americans the world would be a different place. He said they should mind their own business. When I asked Mama, she said I had to be careful what I said about the English and the Americans. Mama said that Abdou was the one who should mind his own business.

After Granny died, Abdou left. Mama closed downstairs and Nesma moved upstairs with us. Everyone stopped coming for lunch. I missed Abdou, but sometimes he came to visit. I would look out of the window after school and see him coming down the street. I would run down and wait for him in the garden. He brought me things. Once he had a bag of ‘asalia. It was like sugar but yellow and healthy. Another time he had roasted watermelon seeds. He even bought me long stalks of sugarcane from the cart that passed through the streets. We ate them in the garden. I waited to see what he would

bring next. Then one day he stopped coming. I waited day after day at the window but never saw him again. No one went downstairs anymore. Mama said it depressed her. It was dark and smelled of Granny. I remember Granny’s smell. Mama said her smell was musky amber. It was an ancient smell. She said Granny’s smell and spirit were trapped downstairs. This meant ghosts. Or maybe the devil, who was also a ghost. Mama was always talking about the devil. They also told us about the devil on TV. If we were naughty the devil would become one with us. I was terrified of the devil and became scared of downstairs. When Nana took me home, we went in from the back door of the house. That was the door to Granny’s floor. I hadn’t been downstairs since she died. Mama was waiting for me. She told me to kiss everyone and go upstairs to my room. When the people left I could come out again. It wasn’t healthy for a little girl to be around so much black. I stayed there for three days. Ever since that day, whenever I come home from school I am frightened to look up. I don’t want to find Nana on her balcony. I am also scared to look at people in black because it might make me sick, but then I peek.

Mama stopped talking about Nesma, but once on the phone I heard her say that she had a dream about her and woke up in tears. After a while she also stopped talking about Baba.

—

Mama never woke up early. I dressed myself. My uniform was on my chair. Mama put it out at night. The socks she left out were odd. One was shorter than the other. I folded the long one inside itself to make it look the same. I went to the kitchen to make my sandwich. I opened the fridge and looked inside. The English girls at school all had apples for lunch. Green ones. Red ones. They bought them from the embassy. We only had apples when we went to Port Said, but they only had red ones. Baba used to drive us some Saturdays. He would buy shaving cream and razors. Mama would buy bars of soap in colored wrappers. The soap from Port Said was better. In Cairo it was big brown blocks cut with a knife. They sold it on the pavement. You had to wash the soap before you used it. I liked the bars from Port Said. They were smooth and pink. They smelled of perfume. They also sold chocolates in Port Said but Mama said they were too expensive. The only chocolate we had in Cairo was filled with caramel that stuck to your teeth. I couldn’t have it because Mama said it was inappropriate for a young girl to be pulling at chocolate. We ate chocolate only when Baba came from a trip and brought back Toblerone. I could have a triangle every Friday. We had been to Port Said the week before Baba left. The apples we bought were finished. Mama had cut them into eighths. She squeezed lemon over them so they wouldn’t turn brown and gave me an eighth after lunch every other day. Sometimes I asked for more but I couldn’t have any because I had to learn restraint. When I asked Mama if we could go back to Port Said when Baba returned, she told me she was busy right now. I also asked if we would go to the beach when Baba came back. She said it would be a long summer and looked away.

Chronicle of a Last Summer

Chronicle of a Last Summer